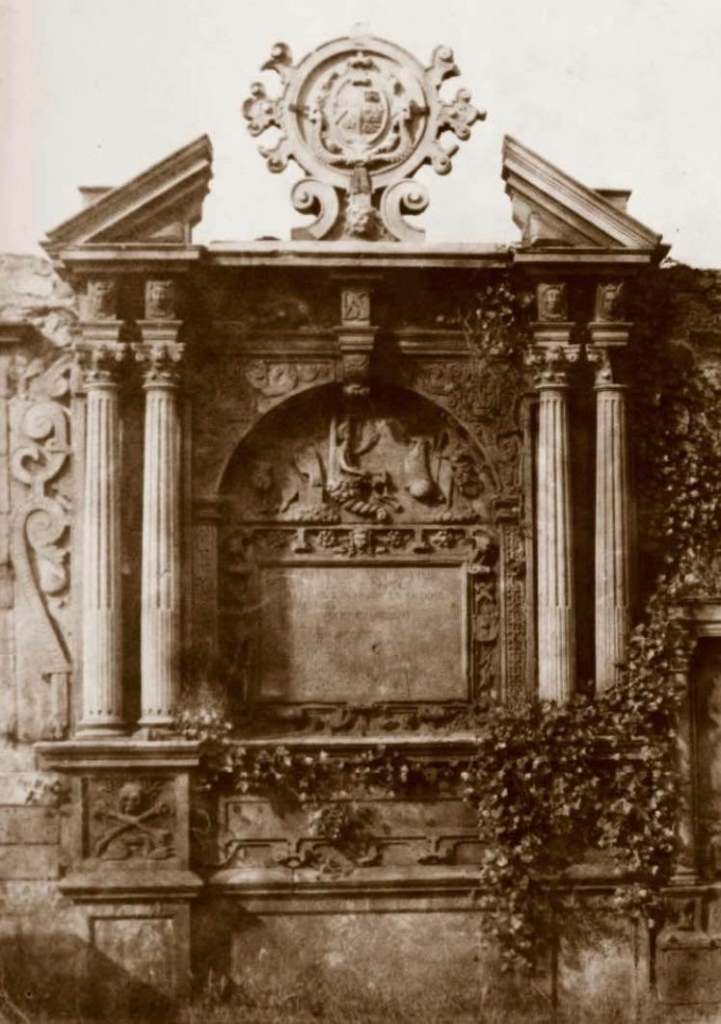

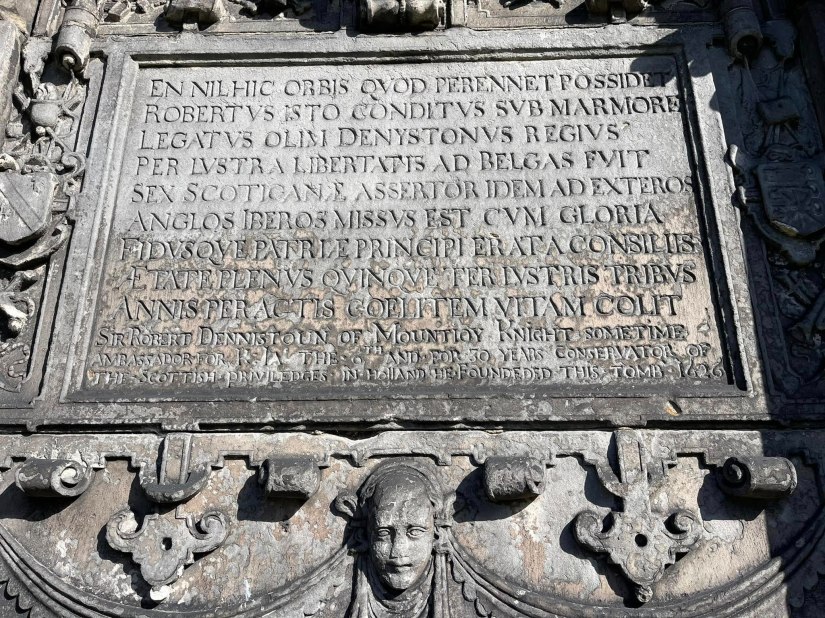

Have you ever noticed that the Cherub in the centre of the top panel on the Foulis Memorial has its eyes closed ? By contrast, the equivalent Cherub on the Bannatyne Memorial has its eyes wide open. Why ?

Whilst here, we should pause to consider just how much is going on on these panels. Being rather high up and difficult to see, it would be easy to miss just how much detail there is on these panels, rich in symbolism and its associated messages. I have added a description on each photo.

You are welcome to challenge or contradict my interpretation of the symbolism. It is a subject that deserves debate.

This scene is flanked by what appears to be pregnant caryatids, perhaps symbolising the promise of new life in heaven. The masked Greenman along the bottom also symbolises new life after death, as does the flowers, foliage, arrangements of fruits and stalks of wheat. The pair of small cherubs in each top corner are blowing trumpets, summoning the dead to arise. The hour glass symbolises that we need to be ready for our time to die, whilst the flaming lamp on top of the hourglass symbolises life going on. The small skull and cross bones, bound with ropes either side bottom corner symbolise what becomes of our mortal remains, which are affixed to the earth. The large Cherub leans rather casually on a skull, showing us to not be fearful of death, but we do need to be ready for it. Ready for it being having repented in time and having been faithful Christians, so deserving of resurrection to heaven. Perhaps the Cherub’s eyes are closed to show how relaxed they are, or how deep in contemplative thought ?

The Chubby Cherub symbolises a healthy new life.

The Cherub on the Bannatyne here has its eyes wide open and staring into the distance. It is surrounded by very similar symbolism to the Foulis, with several added extras. We have the skull and bones beneath the Cherub (we are not fearing death, we are beating it). We have the hourglass (be thee ready for when the time to die comes) and the foliage and wheat (new life). We have a vase full of flower to the left, then a Cityscape of buildings and towers. There is a skull peeking out of one of the windows. A tree grows out of the top of one of the towers (left) whilst the other has a huge lamp on top, from which emits a massive plume of smoke. Another large tree grows behind the Cherub. I suggest this distinctive style is showing us a Cedar of Lebanon, a tree which has held profound significance for millennia. The tree features in the Hebrew Bible, according to which the tree was used in the construction of the Jerusalem Temple by Solomon. To the right of the tree is a cluster of buildings, with what appears to be a large Church in the middle. This could be modelled on St Giles High Kirk in Edinburgh. The Bannatyne Memorial has a Vanitas theme, copying some Dutch artists of a few decades earlier. The symbolism here is clearly heavily influenced by that.